Sea ice extent around Antarctica has hit a record low – for the second summer in a row in the southern hemisphere.

This year’s bottom is 405,000 square miles below the 1981-2010 average minimum area of sea ice around Antarctica. according to the National Snow and Ice Data Center. This amount of ice loss is equivalent to more than half the land area of Alaska.

As Antarctic sea ice shrinks, it paves the way for waves to violently pound the ice shelves that hold back the flow of giant glaciers — some of which are already at risk of breaking up and contributing significantly to sea-level rise, according to the NSIDC.

“Sea ice helps buffer large floating ice shelves and large outlet glaciers such as Pine Island and Thwaites, and if these glaciers begin to lose land ice more rapidly, this could cause a dramatic increase in the rate of sea-level rise before the end of this century,” says Julien Stroev, an NSIDC scientist, quoted in a exemption.

On February 6, 2015, the waters of the Amundsen Sea near Antarctica’s Thwaites and Pine Island glaciers were choked by sea ice, as seen by NASA’s Terra satellite. On February 1, 2023, when sea ice extent was reaching its summer minimum, the Aqua satellite saw very little. (Credit: Images from NASA Worldview, animation by Tom Yulsman)

The satellite imagery animation above shows a striking difference in sea ice extent adjacent to Thwaites and Pine Island glaciers. One image shows ice-choked waters in February 2015, an above-average year. The other was captured in February this year and the amount of sea ice is vanishingly small.

This year’s image also reveals a large iceberg below and right of center. The berg, designated B-22A and currently about four times the size of New York City, broke off from the Thwaites Glacier ice shelf back in March 2002. It then got stuck, or “grounded,” in this relatively shallow part of the Amundsen Sea. For 20 years he remained there – until January, when it started to float away.

Research shows that when grounded, the iceberg played an important role in stabilizing the sea ice in the area. In some years, a group of ground sea ice (also called “fast” ice) remained anchored to the Thwaites Glacier iceberg and ice shelf, helping to strengthen the glacier and slow its flow to the sea, according to NASA.

It’s doomsday No Close, but still…

As the sea ice shrinks and another massive iceberg floats away, the situation becomes increasingly precarious for the glacier, which the media hyperbolically describes labeled “Doomsday Glacier”. Although the doomsday isn’t near (at least not from the glacier!), the Thwaites dump massive amounts of ice into the ocean, contributing about 4 percent of global sea level rise—about 1.5 inches per decade.

Changes in Antarctic ice mass between 2002 and 2020 are depicted in this visualization, with orange and red hues showing areas that have lost ice, while light blue hues show areas with ice accumulation. The loss of ice mass was greatest from the West Antarctic Ice Sheet. The Thwaites and Pine Island glaciers, in the enclosed area, play a major role in draining ice from this part of Antarctica into the sea. (Credit: Screenshot from NASA Visualization Studio animation. Annotation by Tom Yulsman)

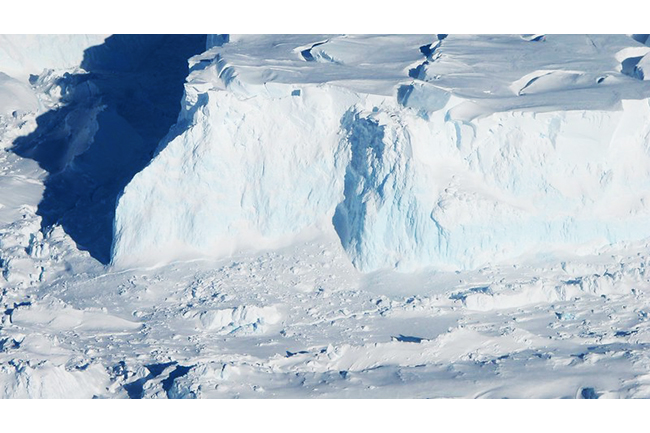

Like a cork in a bottle, the Thwaites Glacier – the size of Florida – helps hold the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, one of only two on the continent. But the cork’s grip is weakening. This happened because the floating ice shelf that extended from the Thwaites Glacier above the water was eaten away from below by warming seawater.

If Thwaites Glacier were to break up, global sea levels would rise by about two feet. This breakup would in turn destabilize much of the rest of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet. It contains enough ice to raise sea levels by more than 10 feet.

Scientists call this “collapse,” but that word is related to the geologic time scale. In reality, sea level rise will play out over centuries.