La Niña usually brings a chill across the globe, and that has certainly been the case during its reign over the past three years. Yet despite the ongoing impact of the climate phenomenon, last month turned out to be one of the warmest Januarys ever recorded globally.

Also, although La Niña exerted its maximum cooling effect in 2022, that year still entered the record books as warmer than 2021. The cause, of course, was man-made climate change.

now, La Niña is fading, and El Niño—which typically warms the climate—has a 60 percent chance of occurring in the fall. So the globe may be on the verge of some very significant warming.

The heat continues

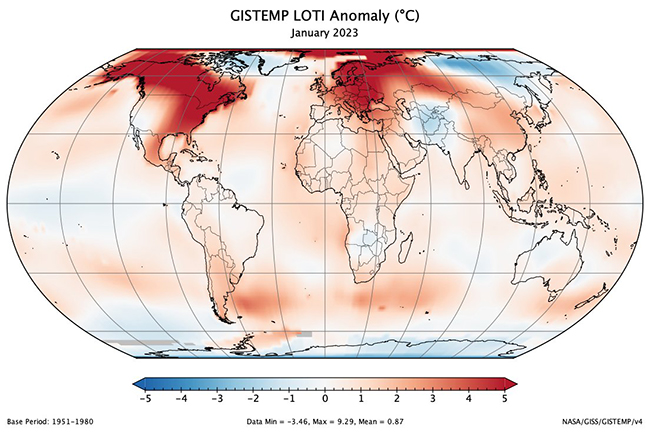

In their latest monthly climate analyses, NASA and NOAA found that last month was the seventh warmest January on record dating back to 1800. “January 2023 marked the 47th consecutive January and the 527th consecutive month with global temperatures, at least nominally, above 20th-century averages,” NOAA notes in its report.

Looking ahead, if El Niño does emerge in the fall, it will likely add its warming influence to human-caused warming. If strong enough, 2024 could overtake 2016 – a strong El Niño year – as the warmest year on record.

In the long term, global surface temperatures have risen thanks to greenhouse gas emissions. But natural factors cause shorter-term ups and downs. Among them are El Niño, which has a temporary warming influence, and La Niña, which has the opposite effect. In this graph, El Niño months are shown in red, including 2016, the warmest year on record dating back to 1800. La Niña months are shown in blue. (Credit: NOAA)

According to a recently published studyA moderate to strong El Niño is actually likely in 2023. “A new global average temperature record could be expected in 2024,” says study co-author Josef Ludescher, a scientist at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. “In the short term, it could even be 1.5°C above the pre-industrial average.” This is a key threshold that almost all nations around the world have pledged to avoid as part of The Paris Agreement.

Exceeding 1.5 degrees C of warming is sometimes presented in the media as the equivalent of diving off a climate cliff. In reality, there is nothing special about this very specific number. The world is not doomed at 1.6 degrees Celsius of warming, but only saved at 1.5.

However, if we rise above 1.5 degrees C and stay there, the risks of extreme heat waves, droughts and rainfall will be significantly higher than they are now, according to 2018 Report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. And above 2 degrees of warming, the risks of very dangerous impacts accelerate.

How close are we to exceeding 1.5 degrees Celsius due to El Niño, even if only temporarily, and what are the chances of that happening?

The global average surface temperature in 2022 (again, when La Niña was exerting its maximum cooling effect) was 1.15 degrees C warmer than the pre-industrial average. In their study, Josef Ludescher and his colleagues predicted that 2023 would bring an additional amount of human-caused warming. To that, they added projected warming from a relatively strong El Niño starting this fall. The result: a 1 in 5 chance of warming exceeding 1.5 degrees C by the end of 2024.

How do La Niña and El Niño affect global temperatures?

La Niña and El Niño are two sides of the climate coin known as the El Niño-Southern Oscillation, or ENSO. And their opposing effects are related to the effects they have on cloud formation.

Let’s look at El Niño first. The natural climate phenomenon is characterized by higher-than-normal sea surface temperatures in the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean, resulting in greater evaporation of water into the atmosphere. As the water vapor rises, it condenses to form masses of billowy clouds, releasing enormous amounts of heat in the process—enough, in fact, to eventually affect the entire globe.

With La Niña, on the other hand, sea surface temperatures in the tropical Pacific cool. This means that less water evaporates from the sea surface, which suppresses cloud formation and results in less heat being released into the atmosphere.

Through a process scientists call teleconnectionsthese El Niño and La Niña impacts are carried thousands of miles across the tropics.

“So the atmosphere warms more during El Niño and less during La Niña, and that affects the global average temperature,” says Mike McFadden, an oceanographer and ENSO expert at NOAA’s Pacific Marine Ecology Laboratory. cited recently in the agency’s ENSO blog.

For every degree Celsius that El Niño cools the surface waters of the central equatorial Pacific, the global average surface temperature of the globe cools by about 0.07 degrees C (0.13 F), according to McFadden. Likewise, for every degree of sea surface warming caused by El Niño, global average surface temperatures rise by about 0.07 degrees C.

“It may not sound like much, but it involves huge heat transfers between the ocean and the atmosphere that affect the entire globe,” he says.

We still don’t know for sure if El Niño is coming in the fall, let alone how strong it might be. In fact, the predictions made at this time of year about what will happen in the fall are quite uncertain.

Even without El Niño, however, a study published on January 30 this year found that we are already on the verge of passing 1.5 degrees C threshold And even if the nations of the world somehow act in concert to reduce greenhouse gas emissions very quickly and aggressively, it is very likely that we will cross the threshold in the early 2030s.

But the researchers found that with aggressive action, we can still avoid the even worse 2 degrees C threshold.

Shall we take this action?