MArijuana is having a moment. Since the mid-term elections, cannabis is legal in about half of the US states – despite getting voted against in three ballots Tuesday in deep red states. Weed is also attracting new investment from entrepreneurs ready to cash in on its popularity, as evidenced by Sean “Diddy” Combs’ recent $185 million purchase of a collection of cannabis retail and production facilities.

There are approximately 10,528 licensed retail stores selling all manner of marijuana, hemp and CBD-related goods in the US today, up from 2,920 in 2018 – and more are popping up in nearly every city where weed is legal. according to research firm Cannabiz Intelligence. Many of these stores see net profit margins between 15-20%, according to Northstar Financial Consulting Group.

Although these brick-and-mortar stores are proliferating, some entrepreneurs say the future of the industry is online. A number of new cannabis tech companies have launched apps and mobile websites in recent years. Some are looking to replicate the Uber-Eats model by helping customers get products delivered straight to their door. Others style themselves after AirBnb and help people rent their homes to cannabis users looking for a place to smoke and sleep.

Although cannabis is not federally legal, tech startups that capitalize on the drug’s ever-growing popularity have the potential to be extremely lucrative businesses. Americans smoke more marijuana than tobacco cigarettes for the first time in history, the legal sales of cannabis in the United States are expected to exceed $57 billion annually by 2030.

Read more: Uhere Marijuana legalization failed in the 2022 midterm elections

Despite the potential growth, entrepreneurs face serious challenges in getting around federal regulations for the sale of cannabis—not to mention that online commerce isn’t always an easy process. “There are certainly potential legal difficulties with these new technologies and business models,” said Alex Kreit, an assistant professor of law at Northern Kentucky University and director of the Center for Addiction Law and Policy. “But many of these firms will have an incentive to try to make their technology compliant with the law.”

How online retail works

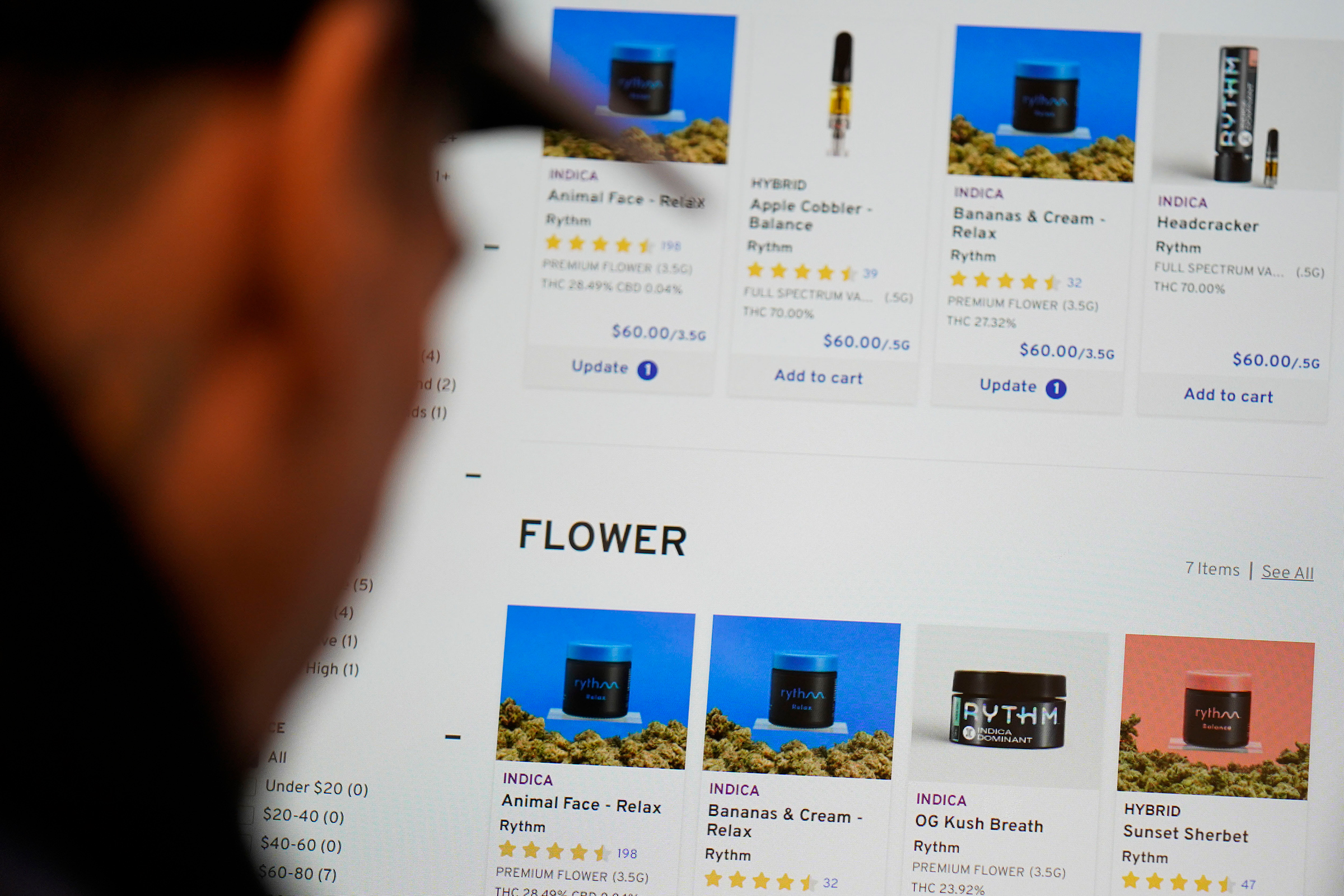

Customers place orders for cannabis products on a tablet at a RISE dispensary in Bloomfield, New Jersey, on April 21.

Seth Wenig—AP

Running a profitable cannabis store can be challenging in the current climate. Small business owners are likely to find that real estate costs are higher, insurance companies may deny them coverage, and competition in stores is intense as many competing cannabis businesses spring up at the same time in places where it is popular. These factors seem to be forcing a growing number of cannabis shops to move online and form partnerships to reach more customers.

“Everything is about to go online,” says Henry Calix, the founder of Weedsies, a Miami-based digital cannabis startup that helps farms reach customers. “A lot [landlords] they don’t want to lease to a dispensary, so instead of opening a brick-and-mortar store, more cannabis farms are also becoming retailers.”

Enter platforms like Weedsies and Leafly. These popular startups don’t grow cannabis or even sell it, but rather connect dispensaries with retail customers through their mobile app and website. It’s like an online weed market where the host provides a space for vendors to trade and sell their products at a lower fee than it costs to run a storefront. And the companies that host these marketplaces are seen as any other technology platform, making their mark on a relatively new industry.

“We are a technology platform that uses our own data and content to connect consumers with the right cannabis products offered by local brands and retailers,” said Yoko Miyashita, CEO of Leafly, a publicly traded online cannabis marketplace with approximately 8 million monthly active users. On Leafly, anyone over the age of 21 can enter a location on its website or app and start browsing cannabis products from vendors across the country that can be purchased if they’re legal in their area. The platform also helps users learn more about a variety of cannabis strains and products, with more than 1.3 million user-generated reviews. Weedsies works in a similar way, but its app is coded using location services, so users can only browse products from vendors if they’re physically located in a state where it’s legal to do so.

Both platforms are inextricably linked to the cannabis industry, but technically they don’t sell any cannabis—and therefore don’t need to hold a retail license, which can cost around $10,000 each year and carries legal restrictions. “Dispensaries use their own cannabis licenses to sell through our platform,” Calix says. “We don’t hold the license in every state.”

Cannabis Culture store in New York on October 21st.

Beata Zawrzel—NurPhoto/Getty Images

However, the legality of selling and supplying cannabis online is complex. Although two more states — Maryland and Missouri — legalized recreational cannabis on Tuesday, bringing the national total to 21, and the District of Columbia, it remains a federal crime to use the drug outside state lines. Someone convicted of crossing a state line with the substance could face up to five years in prison and a fine of up to $250,000 for possession of less than 50 kilograms.

In California, deliveries can be made anywhere in the state, regardless of where the seller is licensed to sell. In order for these transactions to remain legal, online sellers must ensure that they comply with city and state laws before making a delivery. However, some states have tried to curtail the sale of cannabis across state lines. In Oregon, the law requires that deliveries be made within the licensee’s city. “There are places right across the border of a city where cannabis is legal that GPS or technology can’t pick up,” says Kreit, the law professor. “If we have a state-level regulatory regime that limits supply to each locality, that inherently makes it more difficult to comply.”

What the future looks like

Axel Bernabe, chief of staff and senior policy director for the New York City Office of Cannabis Management, smells a cannabis plant during a tour of the Claudine Field Apothecary farm on October 7 in Columbia County, New York.

Michael M. Santiago—Getty Images

The overall national shift in drug policy in recent years has created a number of new protections for marijuana users in some states. The latest protections came Tuesday, when voters in Maryland and Missouri passed ballot measures to legalize the recreational use of marijuana by adults, although voters in Arkansas, North Dakota and South Dakota rejected ballot measures on the issue.

In California, lawmakers passed a bill in late August that would limit companies from punishing employees who use marijuana while off the job. In New York and other states, employers are prohibited from testing their workers for marijuana. And with cannabis likely to be on the ballot again in 2024, it’s possible more states will adopt similar protections in the coming years.

After Tuesday’s vote, about 48 percent of the U.S. population lives in a state where cannabis is fully legalized, and more than 75 percent live in a state where the drug is legal for medical use. In states where recreational cannabis is legal, people can smoke the drug anywhere, and police officers are not allowed to stop and frisk pedestrians based solely on its smell. And legalization efforts could pay off: the industry will add more than 105,000 jobs in the U.S. in 2021, on par with the number of jobs created in the financial sector and the construction industry.

The booming market hasn’t erased some of the difficulties associated with running a cannabis business. “There’s still a stigma around cannabis, even though it’s becoming more normalized,” Calix says. “And even when it is federally legalized, we will likely continue to face this stigma from the banking industry.”

It took six months for Calix to open a bank account for Weedsies, he says, because the banks thought his company was growing and selling cannabis. And some commercial processors still label hemp-derived CBD as a high-risk industry, even though it was federally legalized in 2018 (high-risk merchant accounts pay higher processing fees).

“I thought the best thing to solve a lot of these problems was technology,” Calix says. “Create an online marketplace and allow sellers to promote their brands, promote their products and even sell everything under one roof.”

So far, the model is working — and online cannabis markets could get a big boost if the drug becomes federally legalized, a move the Biden administration appears poised to make after announcing it would overhaul how cannabis is classified under the federal drug code. the drugs.

“Can we be the Amazon of grass?” Leafly CEO Miyashita asks. “Absolutely.”

More election coverage from TIME