After hitting Guam on Wednesday, Super Typhoon Mawar strengthened into one of the most powerful tropical cyclones ever recorded in the month of May.

For a time on Friday, May 26, Mawar howled with maximum sustained winds of 185 mph. This made it the strongest storm of 2023 so far. It’s also stronger than any of the tropical cyclones in 2022. With gusts approaching 210 mph, Mawar pushed waves nearly 65 feet high, according to the Joint Typhoon Warning Center.

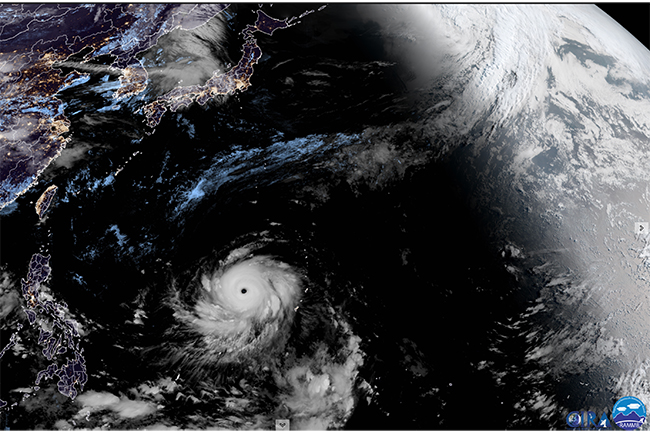

A stunning view of Super Typhoon Mawar churning over the western Pacific as a Category 5 storm on May 26, 2023, as seen by the Himawari-9 satellite. (Credit: CIRA/CSU & JMA/JAXA)

Mawar is our planet’s fifth Category 5 storm of 2023, just short of the 1990-2022 average of 5.3 for the entire calendar year.

“This is an unusually high number of these fiercest tropical cyclones for so early in the year,” says meteorologist Jeff Masters. “With the most active part of the Northern Hemisphere tropical cyclone season yet to come, 2023 may have a chance to challenge the record of 12 Cat 5s in one year set in 1997.”

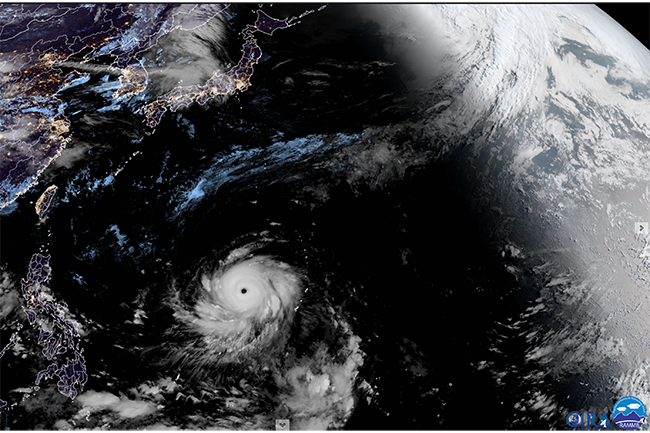

The eye of Super Typhoon Mawar as seen on May 24, 2023 by the Himawari-9 satellite. (Credit: CIRA)

Satellites provide incredible views of Mavar. The close-up animation of the Moor’s eye above is one example. Acquired by the Himawari-9 satellite on May 24, it reveals a phenomenon known as the “stadium effect” that is sometimes seen in strong tropical cyclones. This is a feature of the eyewall—the vertical wall of intense thunderstorms that surrounds the relatively calm eye, which is usually about 25 to 40 miles in diameter.

S stadium effect, towering eyewall clouds curve outward from the surface with height. The appearance is similar to a sports stadium seen from above.

Features known as “mesovortices” are also visible. These mini-cyclones are often found in the eyes of intense tropical cyclones. Wind speeds in them can be up to 10 percent higher than in the eyewall.

Links to climate change

Although it has been challenging for scientists to quantify the effect of a warming climate on tropical cyclones like Mawar, several trends are becoming clear.

The global share of major tropical cyclones — Category 3, 4 and 5 storms — has likely increased over the past 40 years, according to the latest Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (These storms have sustained winds of 111 mph or more.) So is the frequency of rapidly intensifying storms.

There is also “high confidence” that human-caused climate change has contributed to an increase in intense rainfall from tropical cyclones, according to the IPCC. In part, this is because a warmer atmosphere can hold more moisture.

In addition, the IPCC notes that the speed at which tropical cyclones move over the surface has likely slowed, with evidence that anthropogenic climate change has contributed to this effect, at least over the United States. This allows storms to linger longer over an area, leading to heavier rainfall and the potential for catastrophic flooding.

The forecast for Mavar

After reaching sustained winds of 185 mph on Friday, May 26, Mawar began to weaken as it experienced a phenomenon known as eyewall replacement cycle. When this happens, a new eye develops around the old eye.

Once the eyewall replacement is complete, the storm is expected to re-intensify slightly as it churns over warm seas, according to the Joint Typhoon Warning Center. In about three days, as Mawar approaches the vicinity of the Philippine Islands, it will travel over cooler seas and is forecast to weaken.

The storm could threaten the island nation and then possibly Taiwan as well. But at this stage his path is uncertain. Time will tell.