– by a New Deal Democrat

As I mentioned earlier, from time to time I read people who have interesting things to say, even if their worldview is very different from mine. One such person is Mike Shedlock, aka Mish. He’s an aggressive libertarian and has a long track record as a Doomer, but he often analyzes some thought-provoking economic data. It makes me think, even if I don’t end up agreeing, and that’s okay.

As you can imagine, for the past year he has been talking about an ongoing recession. Not so remarkable. But about a week ago, he analyzed Q4 GDP and pointed out that when you take out inventories, real final sales, and in particular real final sales to domestic buyers, look extremely close to recessionary levels.

So I looked and this is what I found.

First, here are the actual final sales (red) and actual final sales to domestic buyers (blue) for the last 8 quarters, both normalized to 0 to their Q4 2022 readings for ease of comparison:

Not exactly brilliant, but not negative either.

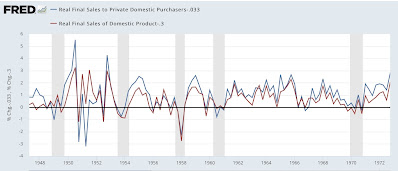

Now let’s look at the historical record, going all the way back to its beginning in 1947. Below I split the series into 3 equivalent time periods, omitting 2020 (so it’s not just spin) and, as with the chart more above , normalizes both series to 0 to their Q4 2022 readings:

There are a lot of false positives (ie recession signals) if we count on only one of the two series being as low Q/Q as it was in Q4 2022. But if we line up when *both* were at such low readings, we get a much more interesting signal.

In *every* recession (of the 12 since the end of WWII) there has been at least one quarter in which both readings were as low or lower than in Q4 2022. Moreover, often both have turned negative 1-3 quarters before the recession started. If we subtract those, there are only 5 false positives and 3 of those are in the late 1940s and 1950s. There have only been 2 false positives in the last 60 years, in 1966 and 1987, which were deep slowdowns that didn’t quite turn into recessions.

So the deep slowdown in real final sales and real final sales to domestic buyers in the fourth quarter tells us that the economy is by no means out of the woods.

One important difference over the years has been how quickly manufacturers have responded to changes in demand by increasing or liquidating inventories. Before 1992 there was a constant and obvious lag:

In other words, suppliers continued to stockpile for a quarter or more after sales declined. To eliminate this backlog, they cut production and also workers on the production line.

Since 1992, with the just-in-time inventory model, often with overseas suppliers, inventory liquidation occurs more quickly and with much less severe impact on sales:

Given the problems with the just-in-time model exposed by the pandemic, producers may return to a more conservative “just in case” model, which will again require a sharper reduction in inventories.

Before the first estimate of Q1 2023 GDP at the end of April, we will get business sales and inventories for January and February, which will give us some insight into what is happening with inventories and whether Q4’s weakness in real final sales was indeed a harbinger of recession.