– by a New Deal Democrat

Almost all of the news in the morning edition about personal income and spending for January was positive.

In nominal terms, personal income rose by +0.6% and personal expenditure rose by 1.8%. The deflator also rose +0.6%, leaving real personal income almost unchanged, and real spending (after rounding) rose 1.1%.

What looked like moderate growth in real personal income suddenly looks very strong (again: a big drop in gas prices can do wonders for inflation-adjusted data!).

This affects one of the matching indicators used by the NBER to calculate whether a recession has begun, real personal income minus transfer receipts:

Again, what looked like tepid growth or even a year-over-year slowdown now looks strong.

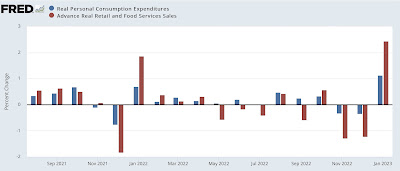

There were only minor revisions over the past few months to personal consumption expenditures, making December -0.2% lower than previously reported. Still, the big increase in January pushed real personal spending to its highest level on record. As I noted earlier, personal spending is like the opposite side of the bargain from actual retail sales. Here’s what the monthly changes look like in each over the last 18 months:

Both had an added dose of seasonality, as large declines in November and December were offset by large increases in January.

The good news also extended to real manufacturing and trade sales for December, which were also updated this morning, jumping 1.5% for the month to their all-time high excluding March 2021 and January 2022 .:

It’s also one of the matching indicators tracked by the NBER, meaning both are now firmly in expansion territory.

The only negative in this morning’s report was that the personal savings rate increased by 0.2% to 4.7%:

While this is good for individual households, because of the saving paradox it is bad for the economy. When overall consumers save more, they spend less, which is negative for the economy as a whole. As the graph above shows, generally as expansions occur, consumers save less. Then, when financial conditions such as interest rates worsen, they tighten their belts and save more. This is what we see now.